Guest post by Dr. Marko Duic MD

At a recent high-school career-night talk where I was invited to discuss medicine as an option, I asked the 11th and 12th grade students why they were possibly considering medicine.

“To save lives” came the unsurprising response. What else would they say?

Later, when I described that my job is not only as an emergency physician but also a department chief—an administrator—they determined that I made less, not more money than I would if I were only an emergency physician, so they asked me why I do it. My answer surprised even me, so I would like to share it.

When the students first told me they wanted to do medicine to “save lives”, I pointed out that we don’t do that in medicine.

Instead, we delay death.

Everyone ends up dying anyway, which would not be the case if we really saved lives. However, by doing our physician work well, we have a chance of giving patients useful time between whatever life-threatening emergency they presented with, and their inevitable later demise.

They asked for an example.

I pointed out that most potentially life-threatening causes of chest pain (MI, PE) are treated with “blood thinners”. But once in a blue moon, and only a few times in the average emergency physician’s career, the parade of usual chest pains for which we give life-prolonging blood thinners, is punctuated by a patient with a very similar but not identical chest pain for which blood thinners could be life-ending: the aortic dissection. It is easy to miss such a patient if one is not paying attention, and if one did miss such a patient, the results could be grim.

So the story I told was of a 48 year old man I had seen six months previously who had had a 55 minute stay in our emergency—including triage, being examined, scanned and transferred to vascular surgery in another hospital. His wife reported that he was discharged a week after surgery, which repaired his dissection that extended from the aortic root to the ileac bifurcation. He was now doing well at home.

Had I saved his life? No, he will die at some point. But maybe he has 10 years until some other grievous atherosclerotic event does end his life.

10 years, 16 useful hours in a day: about 60,000 hours of useful time for this patient, as a result of an excellent team, a great emergency department, and very fast and very careful doctoring.

WOW, the high school students said with admiration. That’s really cool. Or maybe the term was “wicked”.

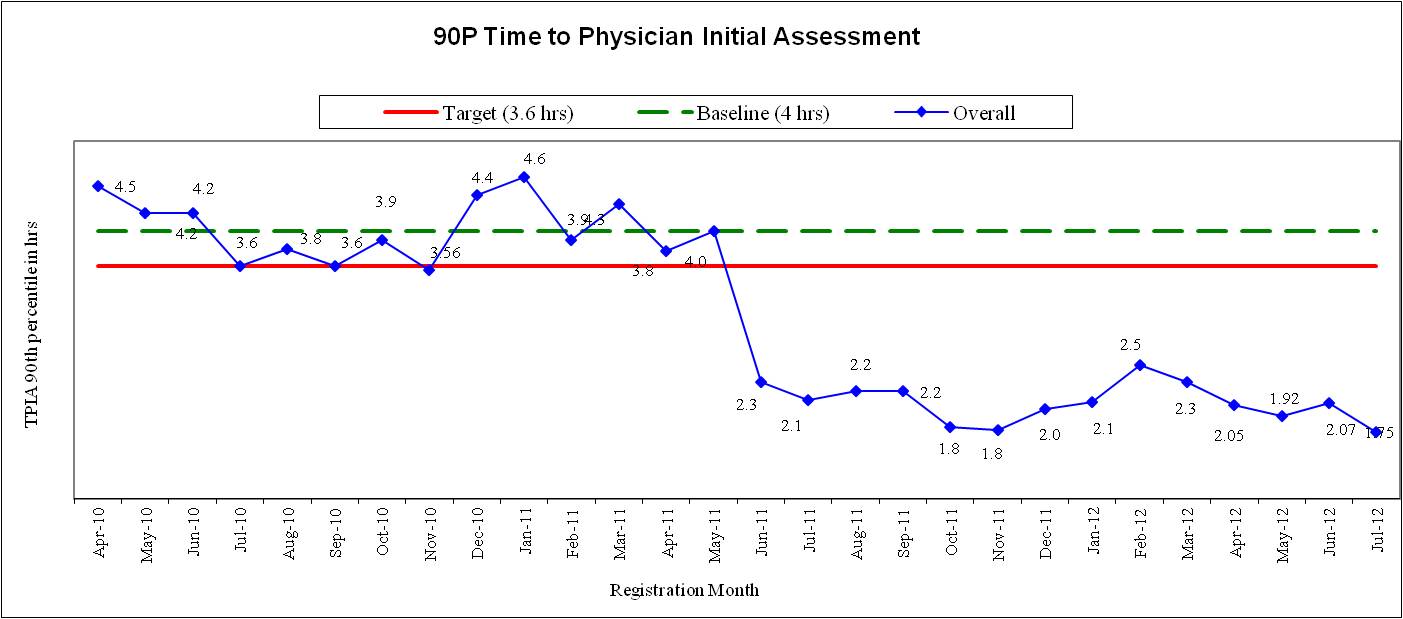

At my hospital, by engaging the team to come up with a leaner flow process, we cut down the average wait for patients by about two hours. The change was planned for months, then put into place overnight on 6 June 2011. On 5 June, patients waited 4 hours at the 90th percentile, and on 6 June and thereafter, they waited 2 hours (posted on this site earlier).

Thus every patient (I told them to keep things simple, although the details are messier) saved 2 hours of useful time.

250 patients/day, 500 hours saved per day. 120 days—one quarter—60,000 hours of useful time have been saved.

Administration for physicians is not as dramatic as “saving a life” as a physician, and filled with much recrimination from all kinds of people with aversion to change, even though it’s clearly an improvement for patients. Yet it’s deeply rewarding when one can “save lives” administratively—allow people who could go live in the community to stop wasting their lives in the waiting room.

As a physician, I can “save a life” once in a while. As an administrator, I can save some life for each patient.