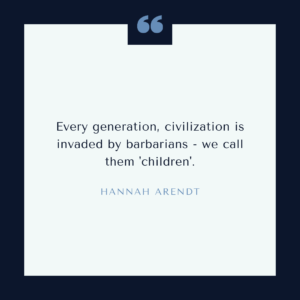

Knowledge grows faster than our capacity to learn. Our own knowledge shrinks as a sliver of the total available.

We risk becoming ignorant, provincial — ideological islands separated from all who disagree.

Look at any recent study. For example, on December 8 the Fraser Institute reported that Canadian patients now wait 27.4 weeks for treatment, the longest ever recorded.

What do you do with this information?

Accept it without question?

Try to digest the research?

Or ignore it, simply because Fraser published the piece?

The Fraser Institute does excellent research, but it challenges most of academia and much of the legacy media.

An Inevitable Age of Ignorance

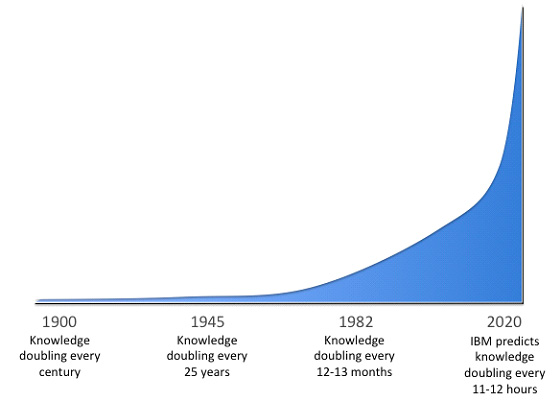

R. Buckminster Fuller proposed the “Knowledge Doubling Curve” in 1982. He noted that in 1900 knowledge doubled every 100 years. By 1945, it doubled every 25 years, and by 1982, it doubled every 12-13 months.

IBM predicted knowledge would double every 12 hours by 2020. (Link for graph). ResearchGate reports there are over 7 million academic papers published each year.

The situation is no better for doctors.

In 2011, medical knowledge doubled every 3.5 years. Researchers predicted it would double every 73 days by 2020.

Pandemic publications prove the point. In the first 10 months of the pandemic, researchers published over 87,500 scientific papers, just about COVID-19.

Specialization

There is too much to know, but it does not scare us as it should. We take comfort in how much we seem to know, or we find ways to convince ourselves we know more than we do.

Until recently, we held back (apparent) ignorance with specialization and shortcuts. Continue reading “Can We Avoid Ignorance?”