Don’t Worry, Be Happy betrays deep wisdom in a simple package. Of course, we cannot be happy by telling ourselves to be so.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy betrays deep wisdom in a simple package. Of course, we cannot be happy by telling ourselves to be so.

The song’s brilliance lies in redirecting our focus. It distracts us from real tragedy and makes us smile.

We do not become happy by focusing on happiness. We find happiness by looking for something else. Happiness sneaks up on us as a by-product of the search.

Quality by Design

System planners manipulate behaviour. For example, product placed at eye level sells more, and kids eat less junk food if cafeterias place healthy options first. Systems influence quality. Check out: Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

System thinking pivots on fascination with The System. It cares much less about individual people inside the system. System thinking solves many problems. But people have uncanny skill at cheating systems, sometimes without even trying.

Babysitting Quality

WestJet treats its pilots like big boys and girls. WestJet does not babysit its front line professionals.

Same thing in university. Many students feel shocked that professors have no interest in spoon-feeding like teachers did in high school. Students soon develop responsibility for their own performance, or fail by mid-term.

Many students form study groups to clarify issues and encourage each other toward higher marks. For them, study groups work.

The Root of all Quality

Medicine is about people, not things. No amount of planning for quality and safety gets around individuals making decisions. And people make decisions for many reasons. Rules, reward, values, concepts, fear of punishment and social pressure can all influence our decisions.

Individual behaviour determines quality, and everyone wants to control it. Government controls rewards; regulators control rules and punishment; educational colleges promote concepts and values (e.g. CanMEDS).

But they all miss the glue that holds these together: relationship. Relationship trades on all spheres of influence.

Professional Relationships

Social structure, stability, and power come from small groups of connected individuals.

Groups of two to four physicians, who meet together regularly to discuss cases, share concerns, and offer support to each other, would create a culture of quality. Community doctors rounding on their in-patients used to meet like this all the time.

NOTE: Groups would need to rotate members every year or so. Quality would suffer if small groups of low performers met together for years.

If system planners wanted to do something really radical, truly innovative, they might encourage small, autonomous groups. Clusters of physicians could keep each other encouraged, accountable and passionate about quality and innovation.

Small groups would out-perform anything that a central authority could put in a guideline or regulation. Physicians who meet and talk together could apply cutting-edge research and knowledge to immediate patient needs. No central authority could ever come close to regulating that kind of service and care.

Small autonomous groups of physicians would make most current regulation redundant, almost comical.

Culture builds from the ground up. Leaders need to nurture, recruit, and develop outstanding culture creators, but ultimately leaders hand over the growth of culture to individuals.

Subversive Groups

Small teams are subversive. By their very nature they have ideas that will not be identical to those held by leadership. This makes some leaders panic.

Any intermediary power, or organization, that forms between the individual and the state, threatens Leviathan. Weak leaders worry about autonomous small groups.

Many large hospitals have gone out of their way to make the doctors’ lounge smaller or less accessible. They do not want doctors talking with colleagues. But informal groups form the basis of culture, society itself.

Square Pegs in Round Holes

Mandating group practices will not build culture. Doctors might organize groups for financial advantage, attend required meetings, but never enter into the relationship building required for culture. Meetings do not create culture. Relationship does. Government cannot build or mend local relationships with practice reform.

Quality does not flow from measurement, rigour, and reporting. These things identify gaps and quantify improvements. They can influence change, but they do not deliver quality per se. We need to learn how to get quality and not just identify when it’s there.

Quality: a Meta Result

Quality, like happiness, comes by focusing on something else. It comes with effort. But quality is more of a second order, meta-result that starts with culture built on relationships.

Blunt regulation, arbitrary legislation, and unilateral action obliterate culture. They drive doctors to despair, to sing Don’t Worry, Be Happy.

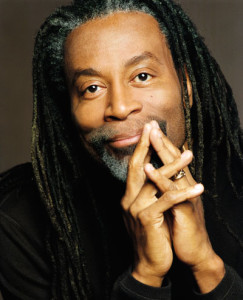

photo credit: bobbymcferrin.com