Victors write history, and medicare is no different.

Victors write history, and medicare is no different.

The vast majority of doctors opposed socialized medicine. As a group, they have been vilified for it ever since.

No one writes books praising doctors in Canada.

Every Canadian schoolboy knows that only the rich got care before 1970. Poor Tommy Douglas almost lost his leg, had it not been for a charitable surgeon.

Medicare saved Canadians from amputations and atrocity. But doctors have been trying to sabotage it with useless services since day one. Andrew Coyne just wrote in March,

“When doctors are paid fee-for-service, they have an incentive to load up patients with services they don’t need; patients, for their part, have neither the incentive nor the expertise to resist. “

Is this comment true? Or is it part of a larger, pernicious lie designed to vilify a once noble and free profession?

I tracked down four doctors who practiced in Ontario before medicare and asked them about their early years:

Were patients left to suffer without care?

What was it like before OHIP?

What’s different now?

Medicine Before Medicare

Dr. S, a GP, practiced for 54 years in a small town in Southwestern Ontario starting in 1965. He offered quick, unfiltered responses filled with facts about his town and patients.

“It was the best job ever. I just loved it.” I “worked 5 days per week with 3 nights in the office until 10 pm….rounds at the hospital everyday at 6:30 [a.m.].”

“Another doc gave all the welfare patients to me.”

“People got good, good care. We accepted every single one. Patients all got equal care. The wealthy patients got the Chief [of staff] to look after them.”

“We knew everyone. The patients were my friends.”

When OHIP came in, “I remember saying ‘This is crazy.’ There should be a user fee. Everything was abused. People went to the emergency department because everything was free…there was absolutely a change. Parents would bring in all 4 or 5 kids even if only one was sick.”

“I just loved it,” he repeated. “I had freedom. I did everything I wanted to do.”

“I never got time off.” I “stopped delivering babies 10 years before retirement…tonsillectomies only shortly before that.”

He worked in “walk-in clinics” near the end. “I would just keep going,” if patients were still there to be seen. Doctors, “Now work 9 to 5 or 8 to 4.” There seems to be “a mindset change…doctors aren’t geared the same way.”

He remembers “…coming home from holidays to do deliveries.” “Everyone did it. We were all solo. You didn’t let people see your patients. You were afraid someone would steal them.” “I had 4,500 patients at one point.”

“Care was really good — it controlled the hours we worked.”

“Absolutely… there was less bureaucracy. It wasn’t there. Not as much then as now.”

Doctors are now “Interviewing patient before accepting them…. just can’t understand it.”

“Patients are more demanding now.” “I would give [narcotics abusers] 3-day prescriptions. Made it harder to sell on the street”.

“It’s a different world now.” But “I just loved it,” and “still keep in touch with many of my patients.”

Dr. B started in 1962 as a GP and practiced for 50 years. He offered friendly, crisp, unfiltered answers. “I have nothing to lose,” he laughed. I struggled to keep up taking notes.

“We saw everyone. No one was ever refused…no one was turned away.” I “collected 67% of my billings. The rest was unpaid.”

“No one was turned away. We did not have medical check-ups. We only saw sick people. Now medicine is kinda boring…calling patients back every 6 months to repeat normal labs.”

When OHIP came in, “My work went up 50%…[it was] crazy.”

“There was no College bothering you. The Chief of staff watched the hospital. We looked after each other.” “We had local discipline.” The “medical care was good.”

“We didn’t spend so much time charting. Now the college has peer review. They want long notes about all the social dynamics.” “The CPSO is the #1 enemy.”

“I worked 7 days per week covering two hospitals. On call every 3rd night and every 3rd weekend.” “I did that until I retired.” There is “more money now,” for less effort.

“What do GPs do now? I used to work in the hospital, assisting, scopes…I did my own tonsils until 20 years ago.” “I was never off…I rarely took time off.”

Dr. H started in 1962 in a larger town and retired in 2017. He gave unhurried answers that pulled in details and anecdotes from almost 60 years of practice.

“I was a refugee from Saskatchewan,” he said and chuckled. “I was worried about things there. So, I came to Ontario.”

“In a strange way, medicare might have become a success because of PSI and AMS [popular pre-medicare insurance companies]. They were MD-run. Doctors trusted them. Medicare was not opposed like it has been in the USA.” “Most patients had insurance.”

I “never refused to see anyone, ever,” because they could not pay. “In the emergency department, obstetrics, the hospital, the office. It was just not an issue. We just saw whoever came.”

He did not recall an increase in demand after OHIP. “I remember one patient who called the doctor for a house call just to see if the doctor would come.” “The majority were too proud to come [to see him] for nothing.”

He noted a deterioration in support and access to “consultations and hospital services”. I used to “pick up the phone and call” a consultant when “a patient needed care, now patients wait for appointments one year from now…You have to plead on your knees for earlier access.”

“There were two big waves of hospital closures… Before that, we did house calls. If a patient needed admission, they would just go. We would send them to admitting. After that, patients couldn’t get into hospital.”

He would say, “You will have to go to the emergency department yourself and sit it out.” “House calls do not make sense for acute patients anymore. I still did them for chronic care.”

To those interested in medicine, he advised, “Get informed consent,” and chuckled again. “It’s not what you think it is. You think you are there to make a diagnosis and prescribe a treatment. Instead, 30% of the time is pushing paper.”

Regarding bureaucracy, he noted that the CPSO was “doctrinal and severe — more severe than the court system.”

“No question: We worked harder.”

Dr C. started in 1953 and practiced for 65 years up North, until 2018. He offered slow, thoughtful responses, mostly because he seemed puzzled and a bit disturbed that I would even ask them in the first place.

When asking whether doctors drove demand for their own services, he said, “Who did you hear that from? [Exasperated] Why would you ever want to see someone who did not need care? Doctors don’t have time for that.” “You must be reading different things,” he said.

“We looked after everybody.”

I said that some people say patients who could not pay were refused care: “That is absolutely false,” he said indignantly. “Some were able to pay, and some weren’t. We looked after everybody.” “Welfare covered the cost partially, but it didn’t pay for operations.” Hospital care was free for them.

The profession “seemed happier overall” when medicare started. Doctors “finally got paid” for all their work. “I was hardly conscious of the fact that things had changed,” when Medicare started. He did not note any change in patient expectations.

In the early years, “Everyone had a family doctor. And we all looked after our own patients.” The ED “…was used very little. It was very quiet. Patients called their own family doctor. The family doc went to their homes.”

“More and more family doctors are not available after hours. They don’t go to the hospitals.” When his patients were in hospital, “My patients loved to see their own doctor. They were so appreciative. I tried to assist in all [their] operations.”

Retiring “was different…[long pause]…I had looked after some patients their whole life…They accepted it. They were sad, but they accepted it.” He chuckled and said, “They knew I had earned it.”

“The vast majority of physicians are stable, honest, and hard working.” They do not look for additional work and have more than enough to do without generating their own business.

Medicine Before Medicare — Summary

These four doctors do not make a study or even a series. But they represent over 200 years of practice. If we add it up in terms of a 37.5-hour work week, they offer closer to 400 years of practice. It would be unwise to dismiss them as anecdotes.

Before medicare, everyone had a physician in many communities. Doctors competed for patients, regardless of whether the patient paid their bills. Around 65-70% of patients paid in full, most of them through the MD-sponsored insurance plans.

Patients got free care in hospital, whether or not physicians got paid. Patients called their own doctors when they felt sick. They did not go to the emergency department or walk-in clinic. Doctors went to patients’ homes and admitted patients directly to hospital.

Physicians worked long hours, with enormous clinical variety, serving patients who needed treatment. Docs spent less time charting or motivating people to pursue healthy lifestyle choices.

Doctors loved to see sick people and treat disease.

Right up until retirement, these doctors saw people who came to see them. They did not go looking for more work to do.

Writers win by bashing doctors. It leads to publication. Academic careers advance. At some point — and I fear that point is long past — it erodes confidence in the whole medical profession. Without confidence — trust — medicine becomes nothing more than technique. And even that tends to ring hollow.

Socialized medicine has created some good things and plenty of disappointments. Blaming doctors for all its problems does not help patients.

What gets us into trouble is not what we don’t know. It’s what we know for sure that just ain’t so.

and

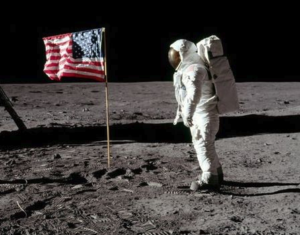

War talk by men who have been to war is always interesting; whereas moon talk by a poet who had not been to the moon is likely to be dull.

Mark Twain

Photo credit:

It will get even worse now that the STAR can publish billings …. doctor vilification will intensify.

Doctors will withdraw,waits will increase,and medical tourism will flourish.

Young docs are compensating by partnering with other young docs !!!! Smart ….

The old (but good) ways are going the way of the dinosaur …. to patients detriment unfortunately.

Good time to skidaddle …..

Good point, as always, Ramunas.

Vilification of doctors goes far beyond hurting doctors’ sensitive feelings. It undermines a physician’s sense of ownership, pride, and duty. We see the same thing in our office staff. We want them to ‘own’ our office, even though they have no name on the deed or lease. They take care of problems; they have pride in the excellent service; they know all your patients; they don’t just punch a clock.

But this sense of ownership is fragile. If I am harsh, unappreciative, or do not work to inspire/encourage this priceless sense of ownership, I can crush it. Once crushed, staff will say, “Fine. Then YOU fix the problem. YOU make the patients happy. I’m just here to work on the computer etc.” If you ruin your staff’s sense of ownership, patient service and office efficiency tanks.

The government/media/bureaucracy/regulators do not understand this. They see doctors as widgets to be allocated and reallocated but in such a way that they ruin the critical elements required to foster/support/encourage excellent medical service.

As you say, “Doctors will [continue to] withdraw…”

Thanks again for reading and posting!

My friend’s father never billed OHIP. He said insurance was between the patient and the insurer and had nothing to do with the provider. His office staff did all the paperwork and then the cheque was sent to the patient, who brought it in. Remember clawbacks? He doesn’t. Same with annual caps. Now you can’t get licensed if you don’t have an OHIP billing number. That is a travesty.

Very interesting, Kathleen. I wonder if he was a psychiatrist? I know that a handful of opted-out psychiatrists were allowed to remain so even after the government made it illegal in Ontario.

When the government/regulator determines a business person’s customers, prices, terms of work, ability to work or not, types of services allowed, payment, reporting requirements, etc., you have full blown socialism. Just because the business person still has their name on the deed to the title of their office/business does not mean that business is private or free in the usual sense of the words.

Hi Shawn

The opting out of ohip was made illegal once dalton won his majority. Those who were already opted out were grandfathered but no one else is allowed. The real question is why OMA never challenged this ruling under the CHA as MDs are supposed be free to be able to opt out.

Brad

Brad!

How did I miss your excellent comment? Sorry about that. I’ve been renovating the cottage like a madman.

Yes, Mcguinty passed the Protecting the Future of Medicare Act in 2004. He made opting out illegal doctors, not just awkward for patients. He also instituted $25,000 fines for anyone caught ‘jumping the queue’. I don’t think anyone has been fined yet.

I agree. This was a heinous move and OMA should have fought it. However, the OMA was solidly under the socialist swing of the governance pendulum at that point. Every so often, people who like freedom and believe that entrepreneurship is not totally evil will run and get elected to the Board. But it is rare. It usually takes a decade of decimation like we saw after the ‘social contract’ years of the 1990s, or the ruthless slander and slashing under Premier Wynne and company to get business minded doctors to sacrifice some time for leadership. Socialists see time served on political organizations as an intrinsic part of their worldview, so they rush to run for elections. Business/freedom minded folks do not see political organizations as such. We wish the political organizations would just leave us alone to get on with our lives. So under socialist-leaning representatives, the OMA at that time thought friendship with government was not enmity with doctors. We have suffered for it ever since.

Thanks again for posting the comment!

Cheers

Doesn’t stop the OMA from challenging it now. No appetite to fight the government but there should be the precedent set that doctors have that ability and that governments shouldn’t be able to pick and choose which aspects of the CHA they obey

PS good luck on the cottage reno

Great point. In fact, I will raise this with my board reps…and you should also. It actually harms the case for those who staunchly favour a one-state-in-control-of-everything system to make it illegal to opt out.

And thanks for the encouragement on the reno’s!

Cheers

I wasn’t around pre-Medicare but I do remember our long-time family doctor, Dr. A Kiss. He made house calls for my sister’s pneumonia and my gastroenteritis. He delivered most of the babies in Welland. He died last week and I’d like to remember him.

Things have changed. I looked for a year to find a family Dr, was interviewed and had to apply. No one is ever in the office and calls cannot be answered. I would definitely rather pay a user fee.

Very sorry to hear about your long-time family doc passing. Sounds like he will be missed (I imagine he retired some time ago).

I am glad to hear you finally found a new doctor. I struggle with ‘interviews’. I don’t agree with screening patients out, but I do agree with trying hard to make a good fit from the start. Things go much better for patients when they have had a chance to ‘meet and greet’ a potential new physician, learn about her hours of availability, hear about what sorts of services the clinic offers, and find out what the doc thinks about chronic narcotics, etc.

Obviously, I am thinking of a community where patients have choice. In a small town where there only is one doctor, she needs to take everyone. I remember one rural doc from a very tiny, isolated, northern community joking with me about having to fire dangerous or unruly patients, “I tried firing them, but they just come back. There’s nowhere else to go!”

Thanks so much for taking time to share this, Martha. I hope you are well!

Cheers

They destroyed the wheel….now they are trying to reinvent it and are managing to screw it up.

One problem is that the “ material” is not the same ….interesting article in the UK’s Daily Mail regarding “ wrapped in cotton wool “ millennial police recruits in the UK , who are shocked to hear that they would have to work nights and weekends, who “ don’t like confrontation” and have an inability to adapt to tough work environments.

Perhaps it was because the doctors of the 60’s, as portrayed in the article , were the offspring of a war hardened generation with a memory of the Great Depression , deprivation and of hard times.

The moderns, in contrast, are the offspring of those who enjoyed the good times of the 60’s and 70’s with snowflakeization being the latest trend.

I loved your line about the wheel, Andris. Brilliant. “They destroyed the wheel…now they are trying to reinvent it…”

I imagine that there is some truth in your “material” comment. However, you seem to offer a balance/subtle-contradiction when you mention the “war hardened generation”. I think that when we accept societal norms that foster softening, we shouldn’t be surprised that some of us become soft. It’s not just a demographic issue; it just happens to show up in a particular demographic, as you mentioned. The societal norms I had in mind include a celebration of epicurean delights; denigration of effort and frugality; and insistence on a substantive equality of outcome in preference to a formal equality of opportunity.

Thanks so much for posting a comment!

PS I deleted your double post and kept the longer of the two, as you mentioned. Thanks again!

One older doctor I was reading about said the clinical gaze has all but disappeared and has been replaced with standards of care and profiling. Older doctors got to know their regular patients as people and took into consideration their personalities with their approach in caring for them. The “clinical gaze”, doctors would notice differences in their patients from appointment to appointment and sometimes noticed things that may require a little investigation and some medical treatment. As you point out that your article is not a study and is more anecdotal. I know in our house where medicine failed in treating, we found successful treatments outside of OHIP and anecdotal accounts from patients who resolved their health issues was important information for our due diligence before proceeding.

Thanks Brian

I like how you juxtaposed “clinical gaze” with “standards of care and profiling.” It’s a favourite topic for me. While I support evidence based guidelines, I find that they too often demand that I ignore a vital bit of information about my patient to make the guideline apply perfectly. We need the ‘clinical gaze’ you mentioned. However if we over-emphasize a gaze/gestalt approach, we risk becoming too far adrift from the standards.

Thanks also for mentioning care and options outside the mainstream. There are many things that can improve health that do not come in a pill bottle.

The quickest way to flunk an exam old days”, was to fail to observe the patient as he or she ( or in between these days) entering the room and to look at them as they spoke.

A few years ago I failed to notice that my female patient suffering from deteriorating pulmonary fibrosis was not carrying her hand bag…her female respirologist ( of my generation) noticed it immediately.

The older generation practiced the the 3 A’s of a successful practice…Ability, Amiability and Availability…the third is fading fast as Martha pointed out.

Great story about the handbag! …and the 3 A’s