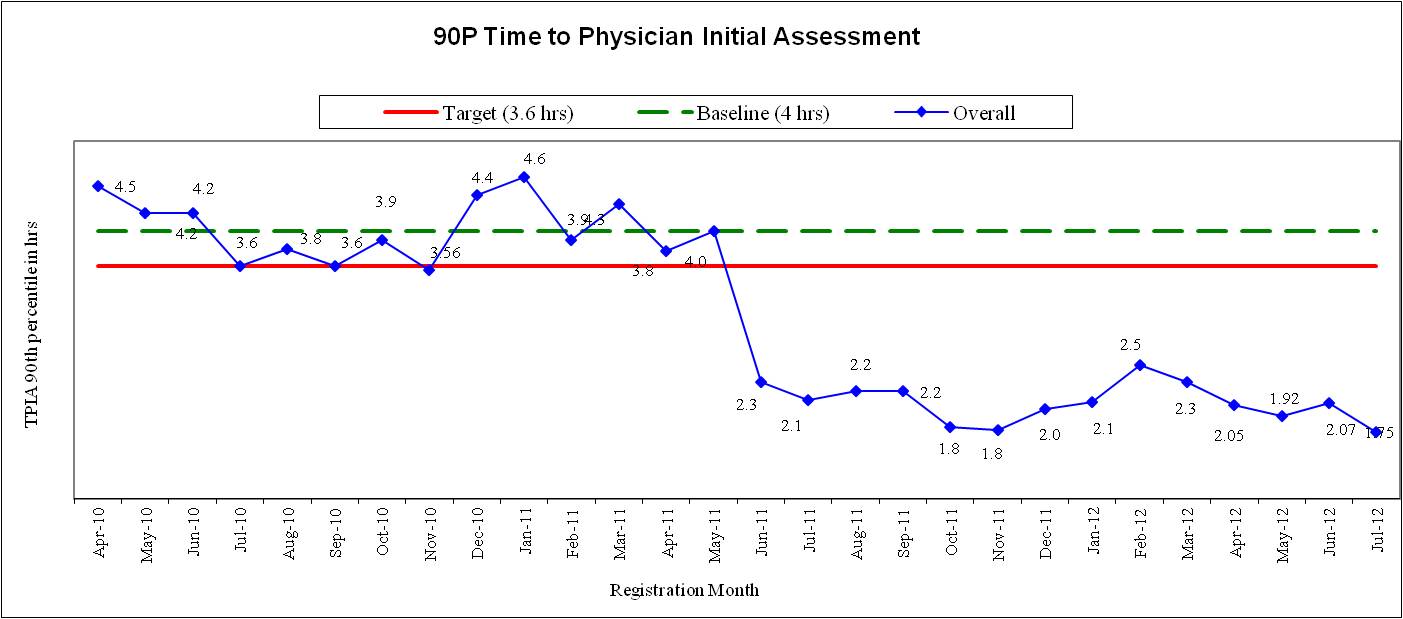

See what happened to our wait times from the first day we closed our waiting room, without spending a penny:

On June 6th, 2011, patient waits plummeted from over 4 hours at the 90th percentile to just over 2 hours when we closed our waiting room. 90th percentile = how long 9 of 10 patients have to wait; it presents the worst case scenario. Today, patients wait less than 60 minutes on average to see a physician – one of the shortest in Ontario.

Physician Initial Assessment includes a complete history and physical examination; not just shaking hands in the corridor or having an alternate care provider see patients.

From day one, the left-without-being-seen rate crashed from 3-4% down to 0.4%.

Hoarding patients in the waiting room – like boarding admitted patients in the ED – prevents patients from receiving the care and treatment they need. If you remove the waiting room reservoir and bring patients straight into the ED, they get seen, diagnosed and treated.

6 keys to success:

1. You need an outstanding team of nurses, physicians, allied health and administrative staff willing to try something new. This can’t be overstated!

2. You need nurses willing to accept working differently. Sometimes there will be crowds of patients; other times there will be none. RNs will need to work together to move patients through when volumes surge instead of moving patients through when the nursing schedule allows. Schedules must match patient volumes by time of day; not the time of day when stretchers open up.

3. Physicians must be willing and able to increase staffing to meet surges in patient volume. MDs must arrive early, stay late or call in their peers for help if patient waiting threatens to exceed targets.

4. Wherever possible, replace stretchers with exam tables. Ambulatory patients can be seen on exam tables and wait in chairs. Stretchers attract admitted patients; stretchers kill patient flow.

5. You need an unlimited capacity mindset. Every patient needs to come inside.

6. Physicians have to get comfortable moving/directing patients into exam rooms and back out into chairs.

We’ll dig into all these points in later posts.

For now, what’s holding you back? Why wouldn’t you want to decrease patient waiting by closing your waiting room?