Over the last year, I served as President of Civitas Canada. Civitas started in 1996 and revolves around an annual conference.

Conference magic cannot be planned. It comes as a surprise. Audience and speakers connect, questions delight, and responses enlighten. Each party comes away encouraged and grateful, not just informed.

The speakers, sponsors, audience, and organizers created something extraordinary at the Vancouver Civitas conference. Better than we could have imagined. I’m so grateful to everyone involved.

Here are my opening remarks (with a few edits). I review ground rules and then try to encourage conversation outside the ordinary.

If want to learn more about Civitas, feel free to write to see if it might be a fit for you.

Welcome to the 28th Annual Civitas Conference. My name is Shawn Whatley, and I’m your president this year.

It is really great to see you all. None of this would be possible without our sponsors. Please join me in a round of applause for our sponsors.

You know, I was very skeptical about a conference in Vancouver…

When I became president, as per tradition, I announced, at a board meeting, that the 2024 conference would be in Vancouver.

The board just stared in silence.

Finally, one person said, “That … is a REALLY bad idea. We will never fill a room … let alone pay for the conference.”

He made the whole planning committee panic.

Thankfully, panic sparked furious activity. And here we are at a SOLD OUT conference!

Thank you so much for coming and being part of this event.

Terms of Engagement

I need to say three things about Civitas — lay the ground rules, as it were.

Our purpose statement says that Civitas exists:

“to promote and deepen understanding through the exchange of a wide range of political, economic, social, religious, cultural, and philosophical ideas concerning the principles and traditions of a free and ordered society.”

Very briefly … let’s unpack three points.

ONE: We are here to learn.

Our purpose statement says, promote and deepen understanding. This means we need to be open, curious, and receptive.

TWO: We are here to be challenged through the exchange of a wide range of ideas.

The broader conservative movement includes a wide mix of ideas. You may be sitting between an anarcho-capitalist, on one side, and a monarchist on the other! This is a fantastic opportunity – don’t let it go to waste.

THREE: We follow the Chatham House Rule.

The identities of the participants are private and all discussions are not to be recorded, reported, attributed, or disseminated in any fashion.

All members and guests are asked to respect this rule.

Without this rule, we could only have conversations that were safe … and superficial. We want to go deep … so we need privacy.

Alright, that sets out our terms of engagement. What do we want to accomplish over the next 1 ½ days?

Goals

I’m hoping we can do two things [this weekend], and avoid one pitfall.

I am a physician and much of my time, over the last 25 years, has been spent in leadership and medical politics.

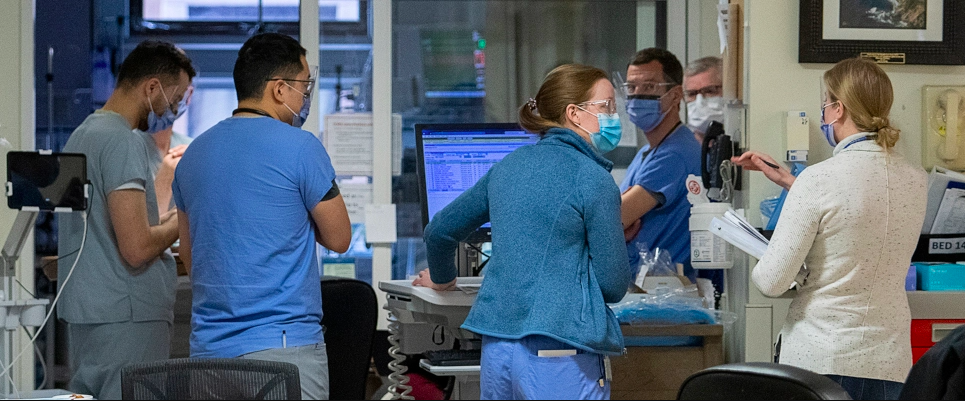

My work has focussed on improving service for patients, while improving the work experience for doctors and nurses.

Improvement means change. For example, you cannot improve wait times, without changing how people work.

But how can you change behaviour? Many of us can’t make our own children behave. How can we make 200 of our colleagues act differently?

Ideas and policy and strategy will not work to change behaviour.

They are not enough.

As Peter Drucker said,

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

We need something more.

In my experience, we need to do two things.

First, we must find a wedge.

Consider emergency medicine. A robust clinical culture shapes care in the emergency department.

Culture is just a set of norms and behaviours. Culture rests on a conceptual apparatus – a whole clinical worldview.

We need to address that worldview and find cracks in it.

The best way to do that is by pointing out bits of reality that do not fit. Think Sesame Street: “One of these things is not like the others…”

For example, we would often say to the doctors and nurses in our emergency department, “Isn’t it interesting how we break all sorts of rules to get timely care for our friends and family? They never wait in the waiting room.”

Then let that comment float; let them ponder it. It takes many similar comments to crack the status quo.

Second, we need to tap people’s internal motivation.

Not just emotion. We need to connect with their internal drive.

For example, we would ask nurses about their experience at triage. They are the wardens of the waiting room. We would ask them to talk about their experience managing a packed waiting room.

It usually took several questions, but they would soon start to tell about people vomiting in buckets for hours or women miscarrying in the waiting room bathroom.

We would just listen.

Eventually, we would ask, “Is this why you went into nursing?”

They would say, “No!”

That is the moment everything changes. Now they want change and are willing to try something new – something better.

In all of this – identifying a wedge, tapping internal motivation – we are attempting to bridge the philosophical gap between theory and practice.

Ideas need to infect people. They need to come alive to shape how people think and see the world.

Our job this weekend is to reflect on each panel and ask: Where is the wedge? And, how can we inspire?

Can we crack open the conceptual apparatus that exists around each issue? What bit of reality does not fit? Think: Sesame Street or cognitive dissonance.

And second, where is the ‘nursing’ question? [“Is this why you went into nursing?”] We must touch the fundamental aspects of human experience.

Example 1 — Finding the wedge

Here’s a quick example of finding a wedge. It’s meant to be fun. Don’t be stressed, if you don’t agree with it.

We opened the conference with applause for our sponsors.

What is applause?

Applause is a public endorsement.

Notice: applause is not transactional.

With applause, we declare that this [sponsorship] is good; not just that it makes us feel good.

It is agathos.

It is part of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful.

But hang on. How can we declare something to be intrinsically Good, in a secular, liberal democracy?

Philosophers across the political spectrum agree that modern liberalism avoids public endorsement of any preconceived Good.

In case you don’t believe me, consider three philosophers.

Starting on the radical left, Slovoj Žižek wrote that,

“[Liberalism] considers any attempt directly to impose a positive Good as the ultimate source of all evil.”

Irving Kristol, godfather of neoconservatism, wrote that

“a keystone of modern liberal secular society” is the impossibility of knowing “what constitutes happiness [the Good] for other people.”

Francis Fukuyama, great defender of liberalism, wrote that now,

“Personal autonomy [includes] the ability to choose the [moral] framework itself,” not just the particulars.

In other words, liberalism seems to say we must not declare anything Good – or at least we must not expect to be taken seriously, if we do.

And yet here we are applauding something we see to be Good.

Perhaps, we misunderstood the nature of applause?

Or we misunderstand the nature of modern liberalism?

Or maybe we misjudged modern society?

Or maybe, society isn’t so liberalised after-all?

Now, this is just an example – something fun. I’m sure you can come up with better ones.

Example 2 — Finding inspiration

Our second task this weekend is much harder. How can we inspire and tap into Canadians’ internal motivation?

Wordsworth tackled this with poetry, during the industrial revolution. He wrote,

“The world is too much with us; late and soon

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers:

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!”

And later in the poem, he writes, “We are out of tune.”

Wordsworth is saying there is more to life than work and money and spending. We waste our talents and become out of touch – out of tune – with those around us: friends, colleagues, family, even with our own bodies.

We need to draw attention to fundamental aspects of the human experience, if we hope to inspire true change.

Aristotle did this by calling us to human excellence: wisdom, courage, self-control, justice. Christian thinkers added faith, hope, charity. We could add generosity, magnanimity, or the Roman liberalitas.

People hunger for these things. They need to hear it in our language.

One pitfall to avoid

Finally, we need to avoid a common pitfall for the right. Roger Scruton called it Hegel’s “labour of the negative”.

The labour of the negative refers to Hegel’s dialectical thought. It is the act of negation repeated relentlessly. Or as Karl Marx put it, “the ruthless critique of everything existing.”

Augusto del Noce, Italian philosopher and specialist on Marx, explains that Marx taught we cannot be free, if we accept anything created by anyone other than ourselves. If we accept anything as a given – even our own biology – we can never be truly free.

We on the right must be careful of adopting a ruthless critique of everything existing. When the left appears to be in control of everything – media, academia, culture – we risk becoming circumspect. As one speaker said at a conference in the US, “They are coming for everything.”

Now this may be true. In fact, it is what we might expect from the Hegelian left. And there is a time to diagnose and identify the negative. But then we need to turn our minds to treatment.

Scruton said it is hard to shift from a labour of the negative to positive, constructive work.

Conclusion

So in summary …

Our job is to find the cracks in the conceptual apparatus that sustains current opinion in each topic area …

… and find ways to inspire change by tapping into people’s internal motivation: “Is this why you went into nursing?”

We need to do these two things while avoiding Hegel’s labour of the negative.