Before medical politics died in Ontario, a PPSA vote meant three hundred doctors from across the province packed into the basement of a hotel in downtown Toronto.

A room full of frowning doctors debating fees was much like kids lighting matches near a haystack.

Inevitably, someone would yell at the board, insult a colleague, or slander the government. Every so often, the Chair would wack away with his gavel, completely ignored by the angry mob.

At one meeting, a red-faced little man stomped several hundred feet across the front of the room and shoved his face in front of another doctor. The angry man had taken offence. He demanded an immediate apology. Or would the other member care to step outside the chamber?

PPSA VotE Needs More Data

The PPSA appears to offer a 1 per cent increase per year with (hopefully) 2.8 per cent in year three.

But what does this mean?

How do specific fee cuts impact income?

Do we have to work 10 per cent harder for a 1 per cent increase?

How does inflation impact the outcome?

How is income impacted by elimination of thresholds and system redesign?

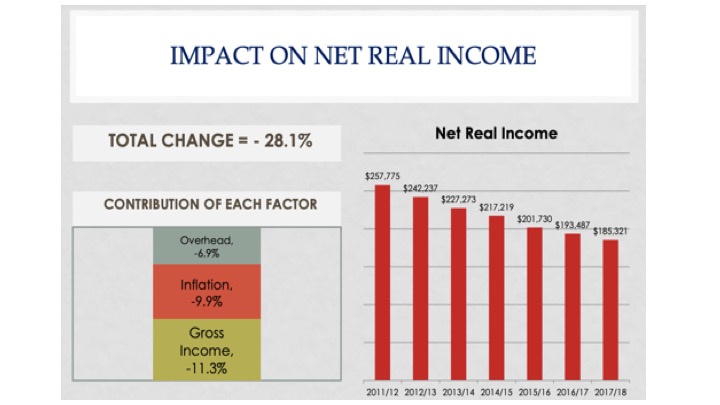

The OMA used to publish fancy graphs of how physician income has changed relative to inflation. The graphs ended when they became too embarrassing.

Governments changed, but OMA performance stayed the same. Endless sub-inflationary increases imposed by successive governments made the OMA look bad.

In 2015, we pushed the OMA to publish an analysis of net income. It showed a steep decline from 2011 to 2015, with an expected 28 per cent cut by 2017-18:

Hazard a Guess At the Cuts Now?

Let’s hope the OMA offers an update. In the meantime, we can try to do our own.

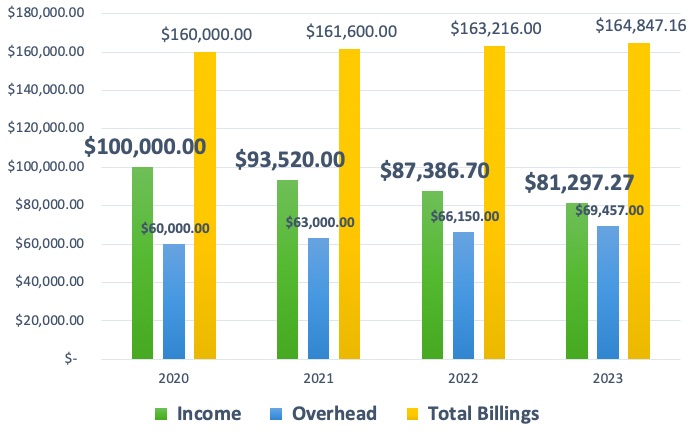

Consider a physician who bills $160,000 and pays $60,000 in overhead (37.5 %). The total billing will increase at 1 per cent for 2021 and 2022, and 2.8 per cent for 2023.

Let’s assume a general inflation rate of 5 per cent. This means office overhead will grow at 5 per cent each year, and spending power (net income) will decrease by 5 per cent each year.

Medical overhead always outpaces inflation, and general inflation may be closer to 7 per cent, but let’s be conservative.

This gives us an 18.7 per cent net decrease over three years. You will feel like you have 20 per cent less to live on. If inflation runs over 5 per cent, a much higher cut seems reasonable.

Add in all the other specific cuts as they apply to your own specialty.

A Fair Process?

Failure to ratify used to mean rolling the dice at arbitration, but at least you got a second chance.

But the chair of the board of arbitration has warned doctors. Do not expect fee increases; arbitration is already fixed.

This makes arbitration a sham.

The whole point of arbitration was to avoid predetermined outcomes. Remove the power imbalance. Enforce fair bargaining. Do not let one side (government) predetermine the price before negotiation even begins.

But Premier Ford made his final offer in Nov 2019. Between May 1, 2020, and April 30, 2023, Ford will pay 1% and not a penny more (Bill 124).

Some think this fair, but does it even make sense?

In 2020, gas was $1.04 per litre. Today, it is $1.70, in S. Ontario. Government wants to fill the medical gas tank at $1.04, plus 1 per cent per year.

Health Reform on the Fly

The proposed contract has far too many silly details to unpack them all: arbitrary limits to practice size, micro-managing office locations, and more. Each detail requires several paragraphs to unpack.

Consider one example.

In the late 1990s, family doctors were a dying breed. Medical students avoided family medicine, and nearly 1.5 million Ontarians could not find a family doc.

Government absolutely refused to increase fees for GP services. Fee for service (FFS) medicine rewards doctors for meeting as many patient needs as possible. It offers no easy way to contain spending.

In the early 2000s, government agreed to increase payments to primary care, but only if government could gain control of costs.

Primary care reform offered the answer.

A basket of patient-enrolment models (FHNs, FHGs, and FHOs) incentivized doctors to roster patients in return for an annual fee. The top rates for an average patient run around $200 per year, to provide a basket of approximately 130 services.

Very few family docs practice FFS medicine any more, although most specialists still do. FFS is bad, according to the experts. It rewards doctors for providing more services. More services mean the government must spend more on care.

Rostered, patient-enrolment models encourage doctors to offer fewer, longer visits, instead of churning patients for multiple return visits. Rostering incentivizes team care and coming up with creative ways to interact and share information without dragging patients back to clinic.

Whereas FFS incentivizes increased visits, rostering is designed to decrease them.

Government has decided it does not like fewer visits after all.

The Ministry of Health wants FFS visit numbers with rostered-payment certainty. Government aspires to 88 visits per week for every 1300 patients rostered. This will incentivize more frequent, shorter visits. It is hard to see how chopping one long visit into three in order to meet government targets will improve quality or care.

How Should You Vote?

It’s not a great offer. But at least it’s only 3 years.

This comes from the OMA negotiations team, in a town hall meeting. It is almost verbatim.

Better accept this offer or else. There is no guarantee of getting half as good at arbitration.

A Hobson’s choice is one which does not offer an alternative: take it or leave it. Unpalatability of the alternative removes real choice.

Closing Thought – Incomes as Information

“Doctors earn enough.”

“You can take the cut.”

I have heard many variations of this modern noblesse oblige. The average doctor lives well enough.

As a physician, you care about your income. It matters to you and your family. But that is not why your income matters to the rest of the world.

Physician income only matters to the extent it impacts patient care.

Does your income attract others to train in your specialty? Do your fees reward you for taking extra call each month?

We want the world to think we would do extra call for free. But it is not true. If people are not paid properly, call schedules become impossible to fill. Emergency departments become short staffed.

I need solid fees in place to guarantee that a vascular surgeon has moved to our area and is eager to answer my call at 3 in the morning. If I have no vascular surgeon, my patient dies.

The PPSA is not about you as a doctor. It’s about whether it is good for patient care.

Does the PPSA build healthcare?

Will your PPSA vote increase care overall or will it undermine the frail shell we have currently?

I cannot in good conscience support this contract. In this PPSA vote, I will vote no.

Photo credit: Pixabay Images Tumisu

Check out Part I: Doctors’ Contracts Are About Central Planning, Not Incomes: Ontario’s PPSA and all the excellent comments!